Underground mysteries

Arched-ceiling cellars are tribute to early masons

By Deb Hadachek – Telescope Editor

www.thebellevilletelescope.com

It’s the architecture underground that draws Jack Hofman to Republic County. The archaeology professor at the University of Kansas digs regularly into the soil at the Pawnee Indian Village State Historic Site at Republic to undercover the round earth lodges and the way of life of an ancient Plains people. But along the way he stumbled onto the more recent underground life of the pioneer settlers that populated the prairie 150 years ago.

Caves. Root cellars. Fraidyholes.

Still solid, with no wood or concrete to support the ceilings. Large stones hewed with precision, carefully laid, designed with artistic niches and cast iron hooks for storage. To Hofman, these are architectural marvels that need to be documented before they disappear. “When you start thinking about these people, they did such creative things with such simple tools,” he says.

“The masons who built them were so thoughtful. They were built to last. They knew they would last.” Hofman and amateur archaeologist Deb Aaron, Hebron, have documented dozens of underground stone structures here.

In particular, the two document caves with arched ceilings, many still perfectly solid more than a century after their construction. Ultimately, he would like to follow the construction styles back to countries like the Czech Republic and Sweden and others where many Republic County citizens trace their ancestries.

Hofman marvels at the labor, the feats of engineering, and the artistry the caves represent. In many cases, they are the only remnant of late 1800s farmsteads dotted around the country. Perhaps most frustrating for Hofman is that he can only guess and make theories about how the caves were built and who built them. No one is alive today who was involved with the construction. He believes masons mounded dirt, laid the stones on top of the mounds, and then dug out the interior of the cellar after it was built. That’s how the wine cellars in Europe were built, he says, and an excavation of a cave he and students did on the Harold Dowell farm north of Cuba bears out that theory.

Hofman documents the stories of people who remember the caves in use—a place to store produce before rural electrification brought refrigeration to the farm. A place to seek shelter as storm raced across the prairies.

But Hofman has a third theory about the caves: Some weren’t originally built just for storage. Some were occupied as the first homes of settlers who came to Kansas shortly after it was granted statehood in 1861. Hofman likes to remind people of a modern age there were no Home Depots to run to for building supplies. “These people were engineers, and they were really amazing.”

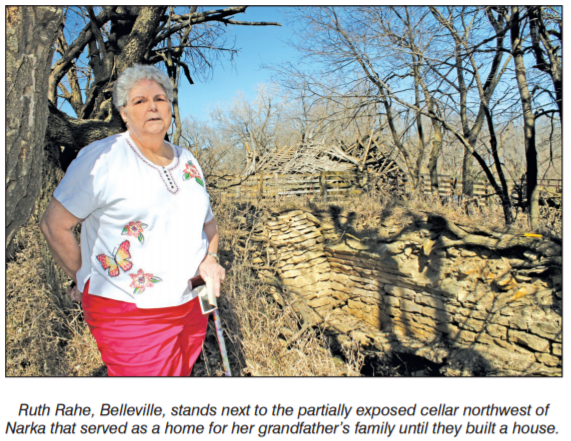

Grandparents’ first home One of those caves is on a farmstead near Mahaska, on the RepublicWashington county line, where the grandparents of Ruth Ocobock Rahe, Belleville, lived. Rahe says her grandparents lived in the cave—maybe for as long as 10 years—while her grandfather helped build the railroad tracks into Narka.

“They eventually had more children than they could sleep in this dugout,” she says, and finally John Hamilton built a house across the road, in Republic County. The nearest post office was in Reynolds NE. Only the walls remain of the dugout today, but signs of meat hooks in the ceiling and wrought iron pieces that supported shelves remain. “When I was a little girl there was still a rock floor on the bottom,” she says. KU archeaology professor Jack Hofman and Butch Gieber, Cuba, examine a stone cave on Gieber’s pasture in western Washington County. Gieber, his son Chad and brother Nick stablized the cave’s entrance and built a protective fence around the structure several years ago for preservation purposes.

Like many stone caves in Republic County, says Hofman, the cave is the last surviving structure of the homestead that once was located at the site. Stone cellars/ Archaeology students excavate sites to learn clues of how they were built

“They had an apple orchard and later used (the cellar) to store apples. “There was another cave under the house,” she says. “I remember they kept butter on a hanging shelf.” Last marker Many of the stone caves, like one east of Cuba on the Washington County line on property owned by the Gieber family, are the last remaining marker of the farmsteads that once dotted the region.

Butch Gieber knows the stone cave in what is now a pasture was built pre-1890, and speculates as early as 1860. The land patent on the farm was obtained by James I. Smith in 1876. “A few years ago my brother Nick and son Chad and I decided we’d better cover it up and put a fence around it to save it,” says Butch Gieber. Like many caves Hofman sees, the Gieber cave opens to the east. “Often it’s the last part of a farmstead still standing,” he says. The caves have vents that were more than just for air circulation.

They were also the way settlers deposited potatoes for storage. “A cave could be the very first thing of substance built,” he says. “Settlers needed storage for hot summers and cold winters.”