Rural Courtland landmark also called ‘old cheese factory’

By Cynthia Scheer – Telescope News www.thebelevilletelescope.com

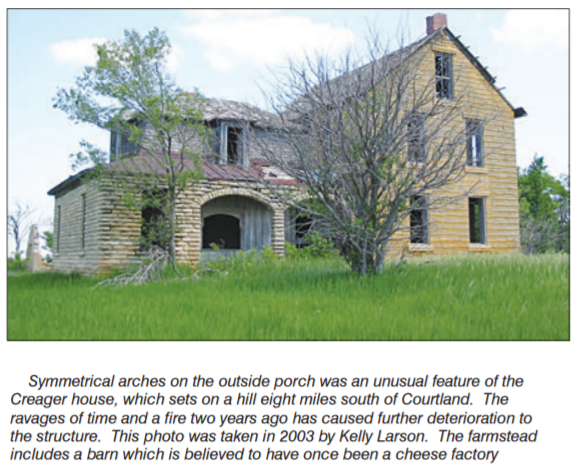

In Republic County’s southwest corner there is an old, falling down stone house and barn that sets along a well-traveled blacktop road. To some, the property is known as “the old cheese factory.” To others the property is referred to as “the Creager House” or “Creager Barn.”

Fifty people – six families – lived in the Creager House, as its known in historical publications, from 1880 to 1940; seven babies were born in the legendary residence.

The 134-year-old building still stands, although a fire two years ago destroyed what was left of the building’s ruined interior; the roof had been gone for years. The crumbling structure, a fireplace salvaged in the 1960s, and memories are all that remain of the once iconic farmstead.

The three-story Creager House sets on top of a hill eight miles south of Courtland. Despite the property’s name, though, the Creager family was not the first to live there.

“Perhaps it became known as the Creager House because of the unusual story of the family,” wrote the late Frances (Larson) Swenson in her publication, “Voices of the Past.”

Swenson’s grandparents, John and Lottie Larson, were one of the families to call the Creager House home.

From the beginning …

The Creager House could be more appropriately called the Smith House. The Smith family built most of the property’s buildings.

The Scandinavian Agricultural Society of Chicago acquired 12 sections of land in Beaver Township – home of the Creager House – which brought many Swedish families to Republic County. The Homestead Act of 1862 was the incentive for many people to move to this area.

According to Swenson, land deeds showed G.V. Smith was granted a deed on Jan. 29, 1881, to land now occupied by the Creager house. The property was identified by a large hill in the southwest corner of the land from which people could see for miles. Views to the south, east and north of the property showed open prairie. To the west was the Salt Marsh. The front yard gently sloped to the bottom of the hill.

A foundation was laid for the Smith’s house as well as an addition to the west to be done at a later time. The stone house was built on the top of the hill from fencepost limestone quarried from the northeast quarter of Section 28, Swenson wrote. The Smiths built several stone buildings, including a barn and outhouse. The barn may have been built fi rst and provided the family’s living quarters until the house was built.

Swenson wrote that each stone “was shaped with exact square corners and expertly dressed with hammer and chisel.” On Aug. 8, 1883, the property became John Swenson’s, who was born in Sweden and raised in Michigan. He would later marry Sarah (Jennie) Arbuthnot and move to Belleville.

John Swenson and Captain Marvin Creager served in the Civil War together.

After the death of his first wife, Creager married John Swenson’s sister, Mary. The couple had two children together: Clementine (Tina) and Marvin, Jr. Creager, who was a generation removed from his family’s arrival to Pennsylvania from Germany, wanted to bring his new family from Michigan to Kansas, but he needed a homesite. Land records in the 1880s show that John Swenson and Creager jointly owned nearly a thousand acres in Beaver Township.

Creager moved to Kansas with his wife, Mary, 37, sons Phil, 14, and Sid, 9, from his first marriage, and Tina, 6, and Marvin, Jr., 1. The family settled into the Smith’s large stone house that Creager and John Swenson owned together.

The Creagers acquired a herd of milk cows and needed laborers to help them. John O. Larson, who was the great-uncle of Eldon Larson, of Belleville, was one of the people in the area who helped milk cows for a while. He would later rent for 16 years the house and land.

Hired help was housed in the upper floor of the two-story chicken house, which was also made of native rock.

“Marvin Kackley, who at one time worked for [Creager] recalls that Captain Creager would come down in the evenings and entertain them with stories of his adventures,” Johnson wrote.

In the 1885 census “M. Creager and John” are listed as joint owners of 960 acres, including 250 acres of corn and 40 acres of oats. The property included 31 horses, 86 milk cows and 80 other cows. No cheese was reported, but 350 pounds of butter had been made. The census showed that the family had planted 140 fruit trees, including 60 peach trees and 40 cherry trees, though none of the trees were producing fruit.

Ten years later in the 1895 census there were 14 trees producing, and another 220 apple trees were planted but not producing fruit. Building an icon The Creagers wanted to enlarge the house the Smith’s built to meet the needs of their family, and they needed to do it before winter. They added an arched-porch two-story addition a few months after they moved to the property.

The original house had two large rooms on the ground level. The Creagers built on a large dining room facing the south with large windows and a fireplace on the north wall. The fireplace was removed from the house in 1969 when Virginia Gustavson Smith, a great-granddaughter of John O. Larson, asked to move the fireplace to her home in Bellevue, Neb. To the west of the dining room was a large bedroom with a large clothing closet, which was rare back then, Swenson wrote.

The stairway leading to the second floor had a banister of highly polished dark wood, possibly mahogany. The second floor of the new addition added two more bedrooms.

Outside the home, the new addition featured a stone front porch with symmetrical double arches of stone.

The famous 138-year-old stone house high on a hill overlooking the Salt Marsh would forever bear their name, but the Creager family would only live there for 15 years. According to research by Frances Larson Swenson in her publication, “Voices of the Past,” “Cap” Creager, as his neighbors called him, went to catch a colt in the pasture on the afternoon of April 29, 1898.

He threw a lasso over the colt’s neck, which spooked it. As the colt ran, the lasso became tangled around Creager’s wrist, and he was dragged for more than a mile. He was pronounced dead at the scene and was buried in Forrest Hill Cemetary in Kansas City. His wife, Mary, remained on the farm for part of the summer before moving to Kansas City to be closer to her children, who were attending the University of Kansas. Clementine “Tina” Creager, the couple’s only daughter, married Dr. C.V. Haggman, a long-time doctor in Scandia. It is her family that still owns the Creager House property.

New tenants.

When Mary Creager moved to Kansas City she rented the farm to Frank Carlson

Carlson, who was born in Sweden, came with his parents to the area. He had been living in Missouri but wanted to return home with his wife, Hilda, and daughter, Emerald. The couple had two more children while living in the house – Violet and Forrest – but left the Creager place in the summer of 1905 when they moved into their newly built home in the southeast quarter of Section 29.

Larson, who was a hired employee of the Creagers, moved in the fall of 1905 into the house with his wife and seven children. The family’s old frame house a mile to the east had only three rooms, and the family needed more space.

According to Swenson, “A six-year-old Larson child described the house as ‘the mansion on the hill.’”

She wrote that when the Larson family moved into the Creager House the boys were ages 18, 16 and 14. The girls, who were 11, 8, 6 and 2, shared the large upstairs bedroom on the west side.

“I have many childhood memories of the Creager House,” Swenson wrote of the stone house her grandparents rented. “A big house with many rooms, a third story off-limits to small children, a long staircase, the hill of buttercups and daisies. Then there were all the family gatherings, which were so special to all of us.”

Her grandfather and his wife, Lottie Samuelson Larson, had each come to America when they were children. Both families spent time in Illinois before settling in Iowa. Larson made several trips to Kansas as a young man and bought a quarter section of land on one of his trips. That piece of land was home for the family until they moved to the Creager place.

Lottie Larson’s parents, Carl and Sara Johanna Samuelson, soon came to live with the family. The elders stayed in the northeast bedroom on the first floor.

“It was there the younger children would gather to enjoy lump sugar and hear stories of life in Sweden, and Grandmother would coach the younger children in memorizing Bible verses,” Swenson wrote

The following March there was a large family gathering in the Creager house. The celebration was in honor of the Samuelsons’ 50th wedding anniversary as well as a wedding reception for one of the newly married Larson sons. Many of the guests stayed overnight in the house. Several more wedding receptions for Larson children were hosted in the house.

August Larson, the second oldest, and his bride, Ella Lundstedt, chose to live with the family in the house for several years. On Oct. 20, 1913, they welcomed a baby boy, Floyd, in the northeast bedroom on the second floor. He was the fourth baby born in the house.

In about 1910 Larsons’ neighbor, Frank Carlson, ran a wire from his house to the Creager House and installed a battery phone in each house. The neighbors could then communicate without leaving their homes

In the 1915 census, there were four generations of the Larson family – 14 people – living in the Creager House. Eight hundred acres of the land was in the pasture and tame grass with the other 100 acres raising a variety of crops including corn, wheat, oats and potatoes. There were 23 horses, 11 mules, 30 cattle, and no mention of fruit trees. Swenson wrote that she thought there may be a water problem at the Creager House because there were one cistern and four wells ranging in depth from 30- 146 feet.

The Larsons lived in the Creager house until 1921 when they moved into a bungalow they built on their original farmstead a mile away.

The Larsons’ youngest son, Gilbert, and his new bride lived in the house and raised three children there. Like all of the children who lived in the Creager House, Gilbert Larson’s children attended Salt Marsh School until it closed in the 1940s.

In 1938 the Gilbert Larson family moved into their aging parents’ bungalow to assist with their care. Gilbert Larson had lived in the Creager house longer than anyone: 33 years.

The final guest

John Williams was the last occupant of the Creager House. He was old and in failing health, Swenson wrote, and a daughter often spent time with him there. He died shortly after he moved into the home.

The last gathering in the house was a Halloween party in the early 1950s, which was attended by young people of the Ada Lutheran Church.

The house was then used to store hay for many years.

The farm belonged to Tina (Creager) Haggman for many years before being passed on to her daughter, the late Ruth Dungan, who lived in Arkansas. For the past 10 years the property has been owned by Dungan’s sons, Robert Dungan, of North Carolina, James Dungan, of Virginia, and Charles Dungan, of Tasmania, Australia.

“As children we went there every summer,” Robert Dungan said. “We plan to keep it in the family.”

Gene Saltzman has rented the property containing the Creager House since 1998. He said the property had previously been rented by the Larson family, including the late Gilbert Larson, the late Darrell Larson, and Darrell Larson’s son, Del.

For nearly a century the Creager House and surrounding property had stayed with the same families, Saltzman said. The property’s owners – the Creager family and its descendants – have kept the land for more than a century while Saltzman said the Larson family rented the land for more than 80 years.

“Those families worked together for a long time,” Saltzman said.

Only stones left

A fire two years ago has left only the house’s stone walls, although even about a third of those have crumbled, Saltzman said.

“When we first moved here from Nebraska about 30 years ago the house needed work, but it was possibly restorable,” Saltzman said. “By the time I started renting it the house roof was leaking, and the ceiling was coming down. My wife, [Lynette], went walking around in there and went upstairs even though I don’t think it was probably safe.”

Robert Dungan said people have expressed interest over the years in purchasing the property and possibly restoring the house, but he said nobody wanted to pay any money for the property, and he didn’t have much confidence in their promise to restore the building.

“I had always hoped somebody would come to us with a valiant attempt [at fixing the property]” he said.

An early morning fire a few years ago caused by intruders destroyed those hopes, Dungan said. Everything but the home’s stones were destroyed.

“I went out early one morning to feed cows while it was still dark and I saw smoke coming out of one of the rooms of the house,” Saltzman said of the blaze.

“There were tracks in the snow going up to the house.”

He said the fire was contained by the fire department, and the damage was minimal. But the fire rekindled by lunch.

“I was on my way back from Jamestown when I saw heavy smoke coming from the area,” he said. “The fire department came back out, but by that time there was nothing left but rock walls.”

He said people have asked to collect some of the fallen stones, but owner Robert Duggan wants all of the stones to stay with the homestead. Saltzman said that he thinks many of the stones have gone missing anyway.

“I think if someone had taken the initiative to restore that building a long time ago it would have really been something,” he said. “It sits on top of a hill, and you can look south across the farmland for a mile.”