The Trost family didn’t hesitate when they got the chance to buy the land of the long-gone town of Minersville. Eldon and Tana Trost bought about 320 acres of the Cloud County side of the old mining property. Their son, Conrad Trost, bought the adjoining place in 1992.

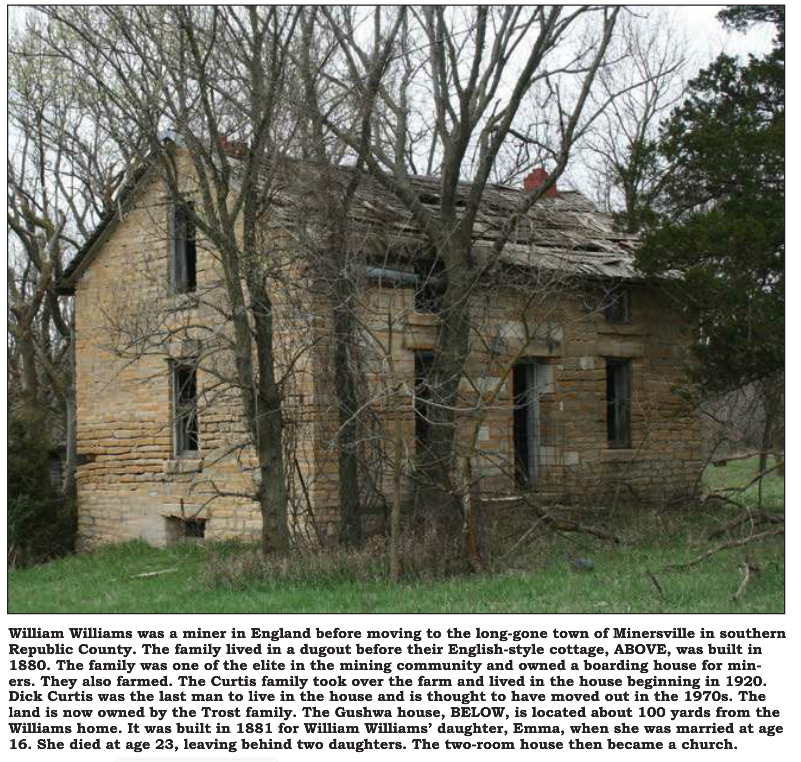

The Trosts’ land came with grazing pasture, which the family needed, but it also came with an abundance of history, including old coal mine piles and several stone houses built more than 130 years ago. One of the stone houses on Conrad Trost’s land is the old Williams Place, sometimes referred to as the Curtis Place. The Williams Place is one of the most recorded in Minersville history.

The story begins with William “Billy” Williams and his wife, Mary Jane, who came from England with their son, Uriah.

According to Agnes Tolbert’s 1963 book, “The Rock Houses of Minersville,” Billy Williams was a miner in England and moved to Pennsylvania with his family to work in the mines. The couple’s three daughters were born in Pennsylvania. The family then moved to Minersville where they lived in a dugout.

“Granny” Williams, as Mary Jane was called, cooked for many of the miners when the family moved to Minersville. Tolbert wrote that she was such a good cook that the miners built her a 50x20foot stone building to be used as a boarding house. The boarding house was built across the gully southwest of where the Williams family’s stone “quaint English-type cottage” would be built in 1880, according to Tolbert. The stone foundation of the boarding house remains.

The English cottage would later be known as “the home of the Curtis boys,” Tolbert added.

When the English cottage was built, Billy Williams brought from his travels an evergreen tree and planted it north of the house near the road. He named the farm, “The Lone Pine Farm.” He later discovered the tree was a cedar, Tolbert wrote.

A large cedar tree still stands just north of the house.

A small stone building is located just behind the house. In “Homeland Horizons” Doris DeweySmith said that behind the house there was a stone smokehouse where meat was cured.

Tana Trost’s father, who was born in 1907 about two miles north of Minersville, knew the Williams family, she said.

“My dad always thought the world of the Williamses,” Tana Trost said.

More than just land

The Minersville property encompassed by the Williams Place has a lot of history for the Trosts.

“Minersville has always been important to our family,” Tana Trost said. “Eldon and I had cattle out there, and on Sunday afternoons when the kids were little we piled into the pickup and went to the pasture to check cattle. We’d walk through the pastures there at Minersville, and I’d take my 35 mm camera. Eldon would find nests of rabbits or meadowlarks and show the kids. We found a horned owls nest out there once, and Eldon boosted the kids up to see it.”

Land records

According to Cloud County land records, Uriah Williams received on May 20, 1862, from the United States government, a patent for 171 acres of land. On April 13, 1883, that land was broken up into two parts. The first part was deeded to Uriah Williams and Delia Williams. The second part was deeded to William and Mary Jane Williams. Land records show many coal leases, including one coal lease on Jan. 17, 1894, from William Williams to William Neitzel.

The Williamses deeded their land with the stone house to Edward Donnelly on March 1, 1900.

Donnelly deeded the land to Seymour F. Curtis on Sept. 7, 1920.

Gushwa House

In 1881 the Williamses’ daughter, Emma, married James A. Gushwa. Billy Williams helped the couple build a two-room house about 100 yards west of the Williams’ family’s house.

Emma Williams Gushwa married at age 16, according to Tolbert’s records, and died in 1888 at age 23. She left behind two young daughters, whom James Gushwa gave to neighbor families to raise before moving away.

Billy Williams then deeded 15×7 rods where the little Gushwa house stood to The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints. The plan was to build a church and lay out a cemetery, Tolbert wrote. The church was never built and the cemetery was never laid out, although there were church services in the Gushwa house.

Part of the small home’s east and north walls still stand.

According to Tolbert, James Gushwa fell under a moving train in the early 1890s and was wheelchair-bound until his death in 1943.

He was known as the man in a wheelchair who sold popcorn in downtown Concordia for many years, Tolbert wrote.

Curtis family takes over

Seymour Franklin Curtis, whom Tolbert said was described as a well clad gentleman of culture and education, moved to Minersville in 1872. He owned 90 acres of land on the north side of Minsersville where the last coal mine was operated in 1940. He owned several mines and was the only person who kept good records of Minersville, Tolbert wrote.

She went on to write that Curtis lived in a “rather special” dugout with a window on each side of the door with lace curtains.

He bought the Knights of Columbus Hall in 1894 and moved his family there until it burned down in 1909. He decided to build a house on his land on the Republic County side of Minersville before he learned that the Williams Place was for sale. The Williams family had moved to Concordia “years before” the Curtis family moved in, according to Tolbert.

Granny’s boarding house became a barn, and the family kept the Williams house, and its lone evergreen tree, just as it was, Tolbert wrote.

Tanna Trost said the Curtis family was still living in the house when she was a girl.

Nobody seems to know when the last Curtis moved out of the house, although some people suspect it was in the 1970s. Dick Curtis was the last surviving member of the family and lived in Concordia for several years before his death in about 1992, according to Gale Longenecker, who managed the Curtis properties for about six years before Dick Curtises’ death.

The other brothers were already dead when I started managing it,” Longenecker said.

The property was a life estate ownership, Longenecker said, and legal documents show Conrad Trost bought the land in 1992 from the estate of Seymour F. Curtis.

The “Curtis boys” never married, Longenecker said, when Dick Curtis died, his attorney went to great work finding heirs to inherit the Curtis family’s money.

“I really thought the state was going to get the money,” Longenecker said. “But they were able to find some distant relatives through the Mormons. I don’t think the heirs ever even knew Dick Curtis.”